The Persecution of Eros' Ralph Ginzburg

Eros publisher Ralph Ginzburg suffered what many consider an outrageous incident of governmental persecution, in which he served time in prison for having exercised his freedom of expression.

What follows is far more than the personality profile of publisher Ralph Ginzburg. It is the recap of an outrageous incident of governmental persecution, in which Ginzburg ultimately served time in prison for having exercised his Constitutional right of freedom of expression. The trial, conviction, and incarceration of Ralph Ginzburg, for publishing an artful, erotic magazine named Eros—a magazine which today would be considered tame and tasteful—was a last-ditch effort by the forces of censorship to repress the sexual revolution which was burgeoning in the early 1960s. The plot against Ginzburg boomeranged, because his persecution was such a blatant violation of Constitutional freedoms that the government was shamed into expanding sexual liberty even beyond Ginzburg's dreams at the time he first published Eros in 1962.

Thus, Ginzburg's ordeal probably had more impact on the sexual revolution than Fannie Hill and Lady Chatterley's Lover combined. Despite the fact that the Ginzburg Case began in the 1960s, it is more than just a piece of old news—a footnote in the history of the American sexual revolution. Ralph Ginzburg had served eight months of a five-year prison sentence for publishing Eros: A Quarterly Review of the Joys of Love.

When asked about how Ginzburg felt angry about the case, he said, "Yeah, sure, I used to feel a little bitter about it. I mean, today you have this deluge of real porn, hard-core stuff, completely vulgar and unaesthetic. And for putting out Eros they fined me $42,000 and sentenced me to five years in prison. I mean, don't get me wrong, I'm glad the pendulum has swung and there's total freedom of expression, my whole life has been a fight against censorship of any kind, but what gets me about it is the sheer hypocrisy of it all. Maybe the people who run this society don't mind vulgar, crude sex—maybe it's just the portrayal of sex as something beautiful and life-affirming that worries them. Maybe that's why Eros was so subversive—because it wasn't ugly or cheap or garish."

Origins of Eros

Photo by Ralph Ginzburg for the Look magazine assignment "A Young Man's Fancy - Model on the Street."

Ginzburg was born in Brooklyn in 1931, the son of Lithuanian immigrants. Like other children of the 30s, Ralph bought the American Dream, warts and all. He also accepted without question the puritan work ethos that imbued Jews and Wasps alike.

After graduation Ralph took a job on the now-defunct New York Daily Compass, left the paper for a two-year stint in the army, and then went to work in 1954 for Look magazine, where his rise was meteoric. Appointed Promotion Manager at the age of twenty-three, he quickly mastered the economics of publishing: "I learned everything there was to learn about selling and distribution, but my heart was always in the editorial department." At the age of twenty-five, Ginzburg was something of a prodigy in New York publishing circles, and even then the literati were a bit baffled by the brash newcomer.

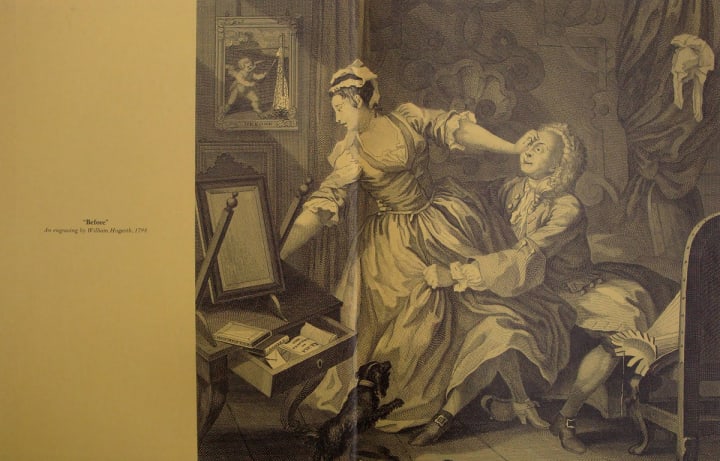

The first issue of Eros appeared on Valentine's Day, 1962. It had been in the works for more than four years, ever since the success of An Unhurried View of Erotica. Eros was a hardcover quarterly with an annual subscription price of $25.00, printed on expensive, heavy stock, and beautifully designed. The critical response to the first issue was overwhelmingly favorable. John Fuller wrote in the Saturday Review that "Eros is a lavish production, full of classical references to art, likely to become known as the American Heritage of the bedroom." The consensus was that only the most hardened and humorless bluenoses would be offended, and nobody even raised the specter of court action to suppress the magazine. Reading a copy of Eros today, you're struck by its decorum, its evasions bordering on coyness, and, above all, its essential gentility. The ultimate effect was about as likely to trigger a hard-on as Little Women, and only the horniest of pubes would ever froth over Eros. But if beauty was in the eye of the beholder, so was obscenity. Ginzburg was heading for big trouble.

The Controversy

When discussing his controversial promotional style, Ginzburg remarked, “To me, promotion was always a means to an end, and the end was to put out a beautiful, important magazine with a philosophy that celebrates life, and enhances it. But guess my promotion talent has been a two-edged sword. It's sold my magazines, but it's also turned a lot of people off me, and caused a lot of trouble. I mean, if Eros had never been advertised, they never would have tried to suppress it. But what was supposed to do–just send copies to my friends and trust in word-of-mouth?"

Exclusively or predominantly Roman Catholic vigilante groups quickly took the lead in the campaign against Eros, and as early as the spring of 1962 their respective publications were running scare stories about Ginzburg's "perverted publication." Priests thundered from the pulpit (occasionally echoed by right-wing fundamentalist Protestants in the Bible Belt) and the Post Office was deluged with letters of protest, many of them written word-forward by whole classes of parochial school kids. The heat was on, and the mortification of Ralph Ginzburg was gaining momentum.

Ralph's office Christmas party in December, 1962, was a pretty tame affair for the nation's most infamous Smut King. No secretary-swapping, just a couple of bottles of Scotch and rye and an FM radio playing classical music. But the festivities were enlivened when two steely-eyed federal marshals walked in to serve Ralph an indictment charging him with 28 violations of the 1873 Comstock Act. The act was named after Anthony Comstock, the most notorious smut-suppressor in American history, and each count of the indictment was punishable by a fine of $10,000 and 10 years in prison, adding up to a maximum penalty of $280,000 in fines and 280 years in prison. Ralph Ginzburg, for the first and possibly last time in his entire life, was speechless.

Ralph immediately retained the best legal counsel he could find. The lawyers quickly pointed out a potentially dangerous aspect of the indictment—Ralph was required to stand trial in Philadelphia. This was the first time in the 90-year history of the Comstock Act that a defendant had been forced to defend himself outside the specific locality where his offense had occurred. Partly due to its large and conservative Roman Catholic population, Philadelphia in the past few years had become the smut-hunting capital of the nation. To celebrate such triumphs over the Antichrist, a giant pyramid of "obscene" books and magazines was set to the torch on the steps of Philadelphia's leading Roman Catholic cathedral, while the city Superintendent of Schools gave his blessing and a boys' choir chorused Gloria in Excelsis in the background. No important church or civic leader spoke out against the officially-sanctioned book burning.

"It didn't take me long to realize it was no accident that I was to be tried in Philadelphia," Ralph recalls. "Two hundred years ago they would have picked Salem."

But by June 17, 1963, when Ralph arrived in Federal Criminal Court in Philadelphia for his trial, he had rekindled his flickering optimism. Partly out of faith in an impartial judiciary, partly from fear of the average Philadelphian, Ralph waived a jury trial and put his fate squarely in the hands of the Honorable Ralph C. Body of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. A slight, graying man of sixty-six, Body hailed from Reading, Pennsylvania and was a local pillar of the American Legion, Rotary Club, and Shriners.

The Trial

As the trial got underway, Ralph received his first jolt. The indictment had named two other of his publications in addition to Eros: Liaison, a weekly digest of sex information heavily laden with pseudoscientific jargon, and The Housewife's Handbook of Selective Promiscuity, a relatively raunchy account of the erotic adventures of an Arizona nymphomaniac named Maxine Serrett. Ralph had expected the prosecution to focus on Eros, but instead, US Attorney Drew O'Keefe virtually ignored Eros and hammered away at Handbook, contending that it was not only pornographic in and of itself but symptomatic of Ginzburg's "intent to pander." It was a shrewd decision, Eros had won so many awards, and had so many defenders in academia and the arts, that it made a tricky target. But Handbook was the weak link in Ginzburg's chain of publications; it was easy to portray as dirty because it was dirty. The prosecution lasted only 87 minutes, and its case was far from impressive, but as excerpt after lubricious excerpt from Handbook was read into the record, Judge Body's lips could be seen growing thinner and thinner, his already florid face flushing redder and redder.

The defense fielded a heavy team of witnesses, including eminent art historians and psychiatrists, Baptist Minister Rev. George Hilsheimer (who nearly drove Judge Body to tears by testifying that he encouraged his Sunday School kids to read A Housewife's Handbook as a valuable exercise in sex education), and Dwight MacDonald, one of the country's leading literary critics. But under the scowling eyes of Judge Body, their eloquent defense of Eros as a social and artistic breakthrough began to reek of eulogy, Long before the defense rested, Ralph knew the verdict.

In his closing statement, Prosecutor O'Keefe charged that "Ginzburg isn't the ordinary furtive smut peddler—he's much worse." Judge Body seemed to nod perceptibly from the bench, and a few hours later found Ralph guilty on all counts. In his decision, he ruled that Liaison "creates a sense of shock, disgust and shame in the average reader," while Eros “has not the slightest redeeming social, artistic, or literary importance or value." He admitted he hadn't read all of A Housewife's Handbook, but said that "the material contained therein is extremely boring, disgusting and shocking to this Court, as well as to an average reader." He sentenced Ralph to five years in prison and fines totaling $42,000.

"I left the courtroom in a state of shock," Ralph remembers. "I still couldn't believe this was happening to me in America." Ginzburg had sensibly steeled himself for a conviction and anticipated a substantial fine, but he never really believed he would be sent to prison, as a first offender with some reputation in the community, the worst he'd expected was a few months suspended sentence. But now he was a convicted felon, with a five-year prison sentence hanging over his head.

The Conviction

Photography by Bert Stern from Eros magazine

On May 26, 1963, Ralph's appeal was denied in the Third Circuit of the United States Court of Appeals by Judge Gerald McLaughlin, who unreservedly upheld Judge Body's decision and refused to reduce the sentence. For Ralph Ginzburg there was now only one barrier between himself and the penitentiary: the United States Supreme Court.

Ralph Ginzburg revered the Warren Court. Its 1954 decision in Brown vs. Board of Education had sounded the death knell of state-sanctioned segregation and paved the way for the civil rights revolution of the sixties, a movement close to Ralph's heart. The Court had also steadily expanded civil liberties in general through a series of decisions such as Miranda and Esposito, which protected criminal defendants from overzealous police and prosecutors, while in Roth it established the same liberalized guidelines on obscenity that enabled Ralph to publish Eros in the first place. His lawyers assured him that it would be unthinkable for the Court to sustain his conviction, by doing so, the liberal majority under Warren would not only be abandoning their own principles but also contradicting and ultimately invalidating their previous decisions.

"He didn't want the Court to just let him off," recalled a friend. "He expected them to give him a medal.”

On March 21, 1966, the United States Supreme Court upheld Ginzburg's conviction by a five to four margin. Ruling against Ginzburg were three of the Court's leading liberals, Chief Justice Earl Warren and Justices William Brennan and Abe Fortas. The majority decision hinged not on the contents of Eros, but on its promotion; the Court held that by applying for mailing permits in the towns of Blue Balls and Intercourse, Pennsylvania, Ginzburg had demonstrated his intent to pander to prurient interests. Such efforts, in addition to his promotional brochures, clearly “stimulated the reader to look for titillation, not for saving intellectual content." The Court, as Robert Stein has written, was "making his style of publishing rather than the material published, the principal crime; in short, Ginzburg was to be jailed for bad taste."

Ralph was stunned by the decision. "It was probably the blackest day in my life," he said. "I mean, to be convicted over a postmark, and one we never even used! That whole decision rested on Blue Balls and Intercourse. I'm willing to admit the application was a mistake—but, my God, since when do you spend five years in prison for a bad joke?"

Ralph received the news of his conviction over the radio in his Manhattan offices. His shock soon turned to anger. "I didn't really know what more I could do, but I wasn't going to just lie down and die decided I'd go out with a fight."

Ralph began waging a war of attrition in the courts. Ginzburg's guilty verdict could no longer be revoked, but it could still be modified, and in a series of impressively argued briefs his attorney applied for a suspension of sentence, or at the very least a sharp reduction of the jail term. The appeals soon bogged down in the strangled dockets of the federal courts, and the years began to slip by with Ralph still a free man.

"By the late 60s," Ralph recalled, "the country was drowning in hard-core porn, and my case began to look ridiculous even to the federal prosecutors." What had begun as a delaying tactic seemed to be turning into a victory, and by 1971 Ralph's attorneys believed there was a strong chance his sentence would be suspended totally.

Avant Garde

Ginzburg’s next creation, Avant Garde, hit stands in 1968. Its promotional barrage was just as relentless as Eros, and to some, at least, just as tasteless. A typical full-page ad showed a girl arched back in bed, eyes closed, mouth gasping in ecstasy, the pitch reads, "Avant Garde, an orgasm of the mind. Total immersion in sensual pleasure. Love on a mink blanket." Old Ralph hadn't lost his touch.

Press reaction to Avant Garde was generally less than enthusiastic, and Time complained that “promise has outrun performance, prudence has conquered prurience, the magazine is more rear guard than avant.”

The magazine never caught on, and Ralph reluctantly suspended it in 1970 to concentrate on his legal problems. But Ralph Ginzburg without a magazine was like Patton without a war, and in 1971 he launched a more modest venture, Moneysworth, a four-page consumer newsletter. If Moneysworth was flimsier than Consumer Reports, it was certainly far more lively, covering everything from "The Wisdom of Maintaining a Secret Swiss Bank Account" to "Best Buys in Dog Food." Ralph's nonpareil promotion made the newsletter a commercial success, but was widely criticized as superficial and occasionally misleading. Moneysworth had been a money-earner, mainly thanks to full page ads in magazines and newspapers across the country, and its profits enabled Ralph to contemplate launching a new version of Avant Garde.

But Ginzburg's different publishing ventures were always shadowed by his legal situation. The long delay in the courts appeared promising, as did the changed attitude of the federal prosecutors, who were making it clear in private that they didn't really want Ralph to go to jail and would welcome some kind of judicial compromise. The climate had changed radically since he was declared a nonperson by the literati in 1966, and by 1971 a number of prominent intellectuals and jurists were not only willing but anxious to champion his cause. Buoyed by the measure of public support he'd wrung out of the intellectual community, and encouraged by his lawyers, Ralph awaited the decision on his appeal with considerable optimism.

Jail Time

But on January 28, 1972, Judge E. Mack Traughtman of Federal District Court dismissed Ginzburg's last plea to vacate, although he did reduce the sentence—from five years in prison to three. It had all fallen apart. He was going to jail.

“Those were dark days," Ralph said, drumming his fingers on the desk. “I felt so fucking angry, and so impotent. For a while, I even thought of fleeing the country, going to Canada. I had my lawyers check and found out that in Canada an obscenity conviction isn't an extraditable offense, and I made some very detailed plans about transferring my funds out of the country, setting up secret bank accounts, and that sort of thing. But finally I decided against it. I hated like hell to give the bastards the satisfaction of seeing me go to jail, but didn't want them to see me run away, either."

On February 17, 1972, his daughter Lark's eleventh birthday, Ralph kissed her and his son, Shepherd, whispered "Fortitude," and drove with his wife Shoshanna to Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, to turn himself into a federal marshal. On the street outside the courthouse he waved a parchment copy of the Bill of Rights before the assembled newsmen, then crumpled it into a ball and flung it into a little basket. "Every day I remain in prison," he said angrily as the flash-bulbs popped, “this Bill of Rights is a meaningless piece of paper." As it turned out, he only served eight months of his three-year sentence before a thoroughly embarrassed Federal government released him.

"Look, what you've got to remember is that just because I advocate open sexuality, because I want people to be free to take any options they want, that doesn't mean lead some sort of Dolce Vita myself. I wouldn't be happy at an orgy. My idea of a great time is lying in bed with my wife, listening to some Bach, just talking into the night about the things that concern us. That's not flamboyant, but it's beautiful."

Maybe it is hard to love a loudmouth, but you don't have to hound him through the courts for 10 years, send him to jail for eight months, and then complain because he won't shut up.

Even Smut Kings have feelings.

About the Creator

Lizzie Boudoir

Thrice married, in love once, overly romantic, and hypersexual.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.